Methods of Practice

|

A wise man will make more opportunities than he finds. Sir Francis Bacon Rather than have hundreds of techniques, the aim of Aikido is to develop the few to high standard. In doing this, it is fortunate that there are many different methods of practice. For example, in theory, all the techniques on the syllabus can be done from suwari-waza, hanmi-handachi-waza, or tachi-waza. Also, many of the basic movements can be duplicated in weapon work. There are also several other useful methods of practice.

Just because O Sensei abandoned kata as a learning methodology does not mean we should dismiss it lightly. It has to be remembered that O Sensei was a great martial artist and learned what he knew in kata based approaches. He only discarded kata once he had absorbed the principles therein.

(b) Static or flowing Static training is where uke clamps on with a tight hold from a static position. Many schools use this method for beginners, yet it remains important for seniors as it provides them with link to basic movement. Once the basics are understood, tori initiates as, or even just before, uke grasps resulting in continuity of flow, or ki-no-nagare. The most important point is to adhere to the principles of movement learned in the basics. If such is ignored and there is no link between static and flow, then one is practising two separate arts that have little in common. The secret lies in combining the two.

(c) Light and heavy Tori and uke can practice light or heavy, fast or slow. Light practice is good for co-ordination, heavy practice is good for technical skill; the two are indispensable for good aiki to develop. In randori or jiyu-waza practice, uke can vary the training, being light, responsive, firm, or downright difficult. A happy medium to aim for is to be somewhere between responsive and firm but it is also imperative to negotiate with uke and practice at either end of the spectrum. One should always try to create training situations that push or stress tori further. Uke should therefore make less obvious attacks, feint attacks, unusual attacks, and while receiving technique should offer various levels of resistance and additional counter attacks; uke should not merely be an overly co-operative teddy-bear for tori to play with. Most importantly, the sooner a freer aspect of training is realised the better. Just sticking to standard forms for five years is not realistic. What is necessary is practice that promotes more movement and the means for tori to learn to compromise under different situations.

(d) Naming the attack or naming the technique When training or grading, some schools of Aikido name the attack, some name the technique, some do both, few do none. Naming the attack means that one is necessarily concerned with dealing with a specific attack, and that it might be approached in several ways with several techniques or variations thereof, adding a degree of spontaneity. Naming the technique means that one must do a certain technique from a variety of attacks, testing the brain. Both these schools create speculative thought. Naming both the attack and the technique, however, robs the student of the opportunity to reflect in the moment. Naming neither is good for humiliation and often produces chaos at lower levels but is obviously the target to aim for. The natural progression in a syllabus would be to, name the attack and the technique, name the technique, name the attack, name neither. |

(e) Three styles of practice

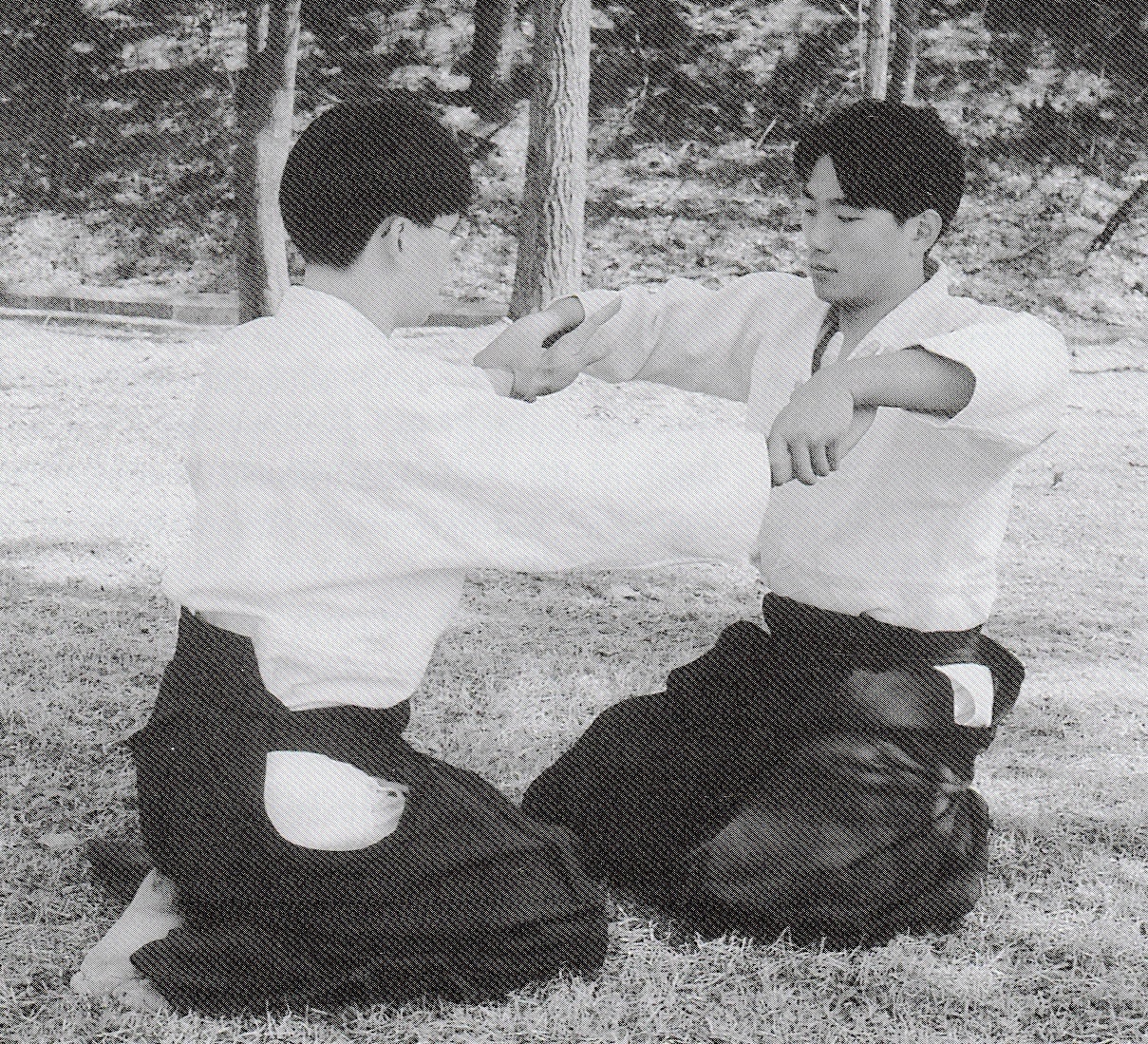

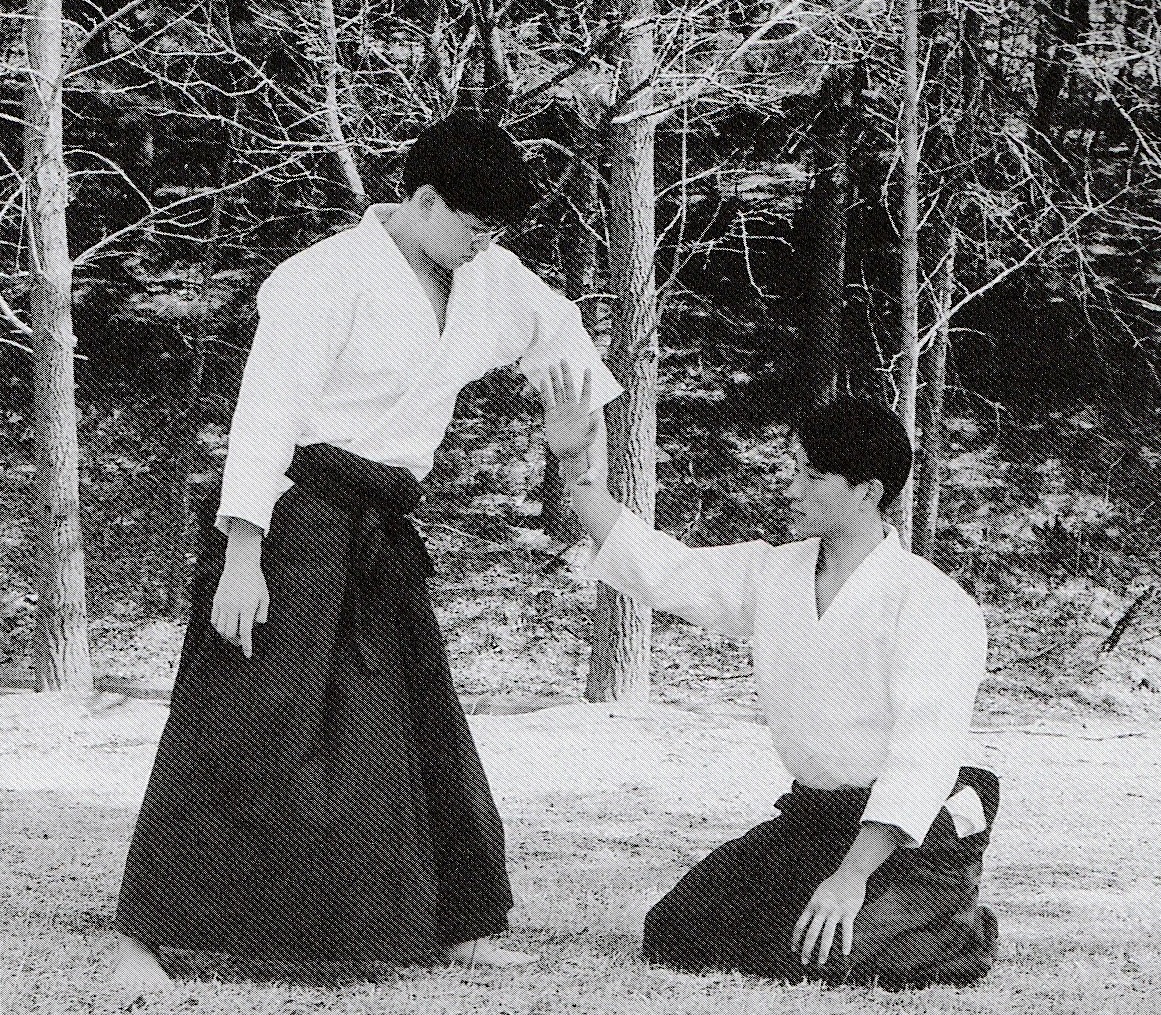

| Suwari-waza | Hanmi handachi-waza |

|

|

|

Performing suwari-waza adds a completely new dimension to moving around for the average westerner. Once accustomed, suwari-waza isolates the legs somewhat from the postural equation and helps develop overall stability. Also noticeable is the fulcrum power generated by the knee just as it lowers to the floor. Of course, this is the point where it is useful to apply the technique and to a less visible extent, it transfers unconsciously into one's tachi-waza. Hanmi-handachi techniques add another dimension and make one aware that whether performing suwari-waza or tachi-waza, one's feet should always be in such a position that it is possible to stand up or sit down quickly and comfortably.

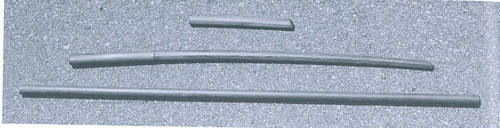

(f) Three weapons

Producing all the techniques against the three weapons, the tanto, bokken, and jo, potentially triples one's repertoire at a stroke, not to mention doing them from kneeling or half standing positions. Practising lots of techniques against a single weapon provides the opportunity to discern strong and weak techniques - one has to be realistic and realise that some are far better than others. Also, practising a similar technique against different weapons allows one to get used to operating at different distances. It also shows how the tactics vary between weapons, both in terms of attack and defence.

(g) Training to the beat

Sometimes a class is just too slow. The teacher clacks two tantos together, or better, uses keisaku, two large pieces of hard wood that monks use for clapping: One clack means one technique, say, shomen-uchi suwari-waza-ikkyo. The teacher waits until all have finished - all students hold at the finish and wait. The teacher clacks again: For the first four times, students perform two irimi and two tenkan variations and the teacher waits until all the students have finished and the room is silent. Tori and uke do not change roles yet. The teacher continues but this time clacks when about half the class have finished. On hearing the clack, all techniques must stop, all ukes must rise and attack toris immediately. The teacher continues for about ten more times, then tori and uke change roles and start again. After it is done, change partners, move onto the next technique, and start again. If on getting to sankyo or yonkyo some students do not know them, just have them do ikkyo again. Finally, continue with a few hanmi-handachi-waza and tachi-waza. It is amazing how much one can get though in a short space of time with this kind of practice.

Another ‘beat’ training method is to follow the rhythm of music. This is particularly useful when training alone. Repeat a certain movement on the left and right alternately for one complete rhythmic song. It is exhausting, and what is practised will infiltrate the sinews thoroughly so be careful to perform only good technique.

(h) Ninin-dori This two-onto-one method of practice adds vigour to Aikido and can be further developed with sannin-dori (three-onto-one) or tanin-dori (multiple attack). Rather than being a test, this kind of practice should be used to develop skill. The practice can be varied in several simple ways and each time it is useful to concentrate on one aspect only. For example: no attacks - ukes walk forward, tori evades; only one uke allowed to attack at a time, slowly; tori names the attack; the teacher names the attack; ukes choose one attack each then stick with that same attack; ukes all use striking attacks; ukes all use grabbing attacks; tori tries to do the same technique to different specified attacks; tori tries to do as many different techniques as possible from one method of attack; ukes and tori are free to do whatever they like. Obviously, the latter is the goal but a structured route will help tremendously. Also practised in Aikido are escapes from morote-dori when held by two people. These techniques are not easy and force one to keep one’s centre while using both hands. Every teacher seems to have their own collection but they are rarely shown – make sure to remember them if seen.

(i) Renraku-waza and kaeshi-waza Practising renraku-waza (combinations) and kaeshi-waza (reversals or counters) are other interesting methods of practice. Not often taught, renraku-waza link techniques together in logical progression. Rarely done are kaeshi-waza. Some say O Sensei taught them only to his senior students. Obviously, such training is more common in a sporting style such as Judo. Further, Shodokan Aikido, the competitive style, has its very own kaeshi-kata. One reason renraku-waza are not generally taught so much might be because of the prevalent idea that the main technique is supposed to work, and that if it does not, one should figure out why rather than switching to an easier technique. There is some logic here, but it is wishful thinking to assume that one technique is always going to work. Accordingly, train with reality in mind and vary technique per the situation.

(j) Free practice Otherwise known as randori or jiyu-waza, free practice can mean anything from allowing the students a little time to do whatever they want to do, to plonking them in the middle of the mat and telling them to do tanin-dori against any attack. In Shodokan Aikido or Judo, randori is fighting. In traditional Aikido it is usually referred to as jiyu-waza, where tori is free to do anything. Naturally, true free practice is excellent for the students. Typically, free practice is done towards the end of the class and students will practice what they have studied that day. Other times they can do whatever they like. In this way, tori and uke can negotiate their Aikido training rather than always have it dictated to them by the teacher.

(k) Competition After about three weeks of any style of traditional Aikido the average beginner will no doubt begin to learn and espouse the idea that competition is against Aikido principles. They will soon learn to support their stance with the argument that many Judo forms have disappeared since it entered the Olympics etc, or that sport Karate without kata has lost its essence. What is amazing is that before starting Aikido these very same people played soccer, tennis, or whatever and greatly enjoyed themselves, and probably still do. It is quite amazing how gullible and irrational the human mind can be. We are all competitive and we all bring it with us to the dojo. In our society, it is natural. That being said, in the dojo, to an extent, we are like the monk in the temple who tries to forget the external world. Not easy, perhaps not even rational, but a goal nevertheless. By not competing in Aikido we have the chance to develop our ability to a higher level through co-operation. However, if the ultimate purpose, fighting, is ignored or forgotten, we may lose direction. In Aikido then, the way we test ourselves is to make strong attacks when striking or grabbing. Of course, at times this can turn into a friendly kind of competition where uke tries to clobber tori or grab them so strongly that they cannot move. When martial art becomes sport the main problem is that the committed attack vanishes as both parties become overly cautious in their desire not to be caught off-guard or off-balance. Competition as we know it, with form and rules, complicates the art as it overly prescribes the method in which we train. If competition is the way one wishes to go, then what is needed is a broader training program that includes the traditional method and also covers every competition-illegal technique to be found; techniques are illegal in competition because they are dangerous, and they are dangerous because they work, but they can only be dangerous if one is good at them. If they are not practised because they are dangerous, then one is not practising a martial art – perhaps it could be called a martial sport. So, in the case of say, Shodokan Aikido, the competitive form of Aikido, whether it is indeed sport or art can only be determined by how one trains, not whether one enters competition.

(l) Misogi Some teachers hold a particularly gruelling class and call it misogi, or spiritual cleansing. Typically, one does the same thing, like shomen-uchi with a bokken, for the whole lesson. Two things happen here, either one’s technique gets progressively worse, or it improves. The whole point of the ordeal is developing the mental determination to continue in the face of adversity – overcoming fatigue and pain. In terms of technical development, however, there is a danger that it can have a very detrimental effect on technique since it is when one is exhausted that what one really knows comes out, or worse, what one is doing really sinks in. If one is making bad technique, this will obviously be training a bad habit. If one can overcome the pain and continue to push out good technique then it will have a very positive effect – one will be able to produce good technique under stress. A more modern training method ought to dictate that one stop when the technique worsens – yet many would give up too soon. The most useful benefit of misogi training in terms of technique is to move from the learned to the acquired – but will only have a positive outcome if the technique is performed consistently well.

(m) Centre to centre Tori and uke place a jo (staff) between their centres and take it in turns pushing each other slowly and strongly across the mat. The aim is to become aware of initiating strong movement from the centre while maintaining balance and posture. If you find it painful to hold/push the jo strongly, put a book against your belly to dissipate the force of the push thereby allowing you push even more strongly. Also, if one partner seems much stronger than the other, give the weaker one the book and see how much they instantly improve! When moving onto technique, say ikkyo, draw your attention to the jo exercise - do the technique with the same kind of push-feeling, as though pushing uke from your centre rather than through the arms. Likewise, uke should coordinate his attack by moving centre and striking arm in unison.

(n) Play Aikido can be great fun and it is not too difficult to invent interesting methods of practice. Some interesting play ideas follow:

1 From shizen hontai partners push each other until one moves a foot, the object being, not to move. This can be varied by taking it in turns to attack and defend, or having both attack together. More fun can be added by allowing pulling. 2 Both partners walk towards each other along a line on the tatami, the object being to walk through each other. Obviously, one partner needs to be pushed off the line, allowing the other to continue straight ahead maintaining composure. Sometimes, both fall off the line. To make good practice, make it a rule that the forward walking movement cannot stop. This leads to a quick, dynamic decision. 3 Make a Sumo ring with belts. With jackets on or off, push partners out of the ring, or make any part of their body touch the floor. 4 Sit facing partners as in suwari-waza kokyu-ho. Simply, partners push each other over at the same time by any means whatsoever. Backwards can be dangerous if the person is not flexible. Pulling could also be allowed. 5 Facing partners in a press-up position, try to knock one's partner's arms away, making them fall down on their bellies, or faces if not careful. 6 Have students put a tanto or a piece of paper in their belts at the rear. Students now have to run around and collect as many tantos (or papers) as possible. Creates an almost battlefield like situation and develops an idea of strategy. 7 Sometimes done in Judo is a game where two people try to steal each other's belts, standing, kneeling, or both. The wise teacher tells all the students to put their hands on their heads before explaining the activity. This means they cannot suddenly tighten their belts! A useful rule is not to deliberately touch your own belt. 8 Two students run and clash into each other. Uke tries to maintain their post-clash position for a second or two, which gives tori the opportunity to recognise a shape to take advantage of to form into a technique. With any game it is best to keep rules really simple. Only make them more complicated after everyone has a clear understanding of what they are doing. The teacher's responsibility is to make sure it does not get too rough. The teacher has to create a sense of fun, but maintain control. Accordingly, it is not a good idea for the teacher to join in. * Some more methods can be seen in the section on Strategy, especially the last section. Also, check out the chapters on Aiki, Ukemi, and Resistance. |