Principles

|

Things should be made as simple as possible, but not any simpler. Albert Einstein

It is the principles we should be searching for; they are the same in each art. No art has a monopoly on the principles, although certain arts might be said to emphasise certain principles. The principles determine the form, of which there are many variations. It is therefore strange that it is usually the forms that determine the art. This has to be a mistake. If we research the principles, then there can be no determining the forms. If you search for the principles, and come to understand them, your forms will be limitless.

(a) From technique to principle For some, Aikido techniques themselves are principles; this cannot be argued. Here though, I look for principles within the techniques. A principle is a common movement, shape, or feeling discernible across a range of techniques. To learn Aikido efficiently it is useful to identify certain common principles, collect them, study them, test them, and apply them. In the broad sense ikkyo, that famous first technique of Aikido, could be a principle, but here, as it is ikkyo itself that proves so difficult to fathom, it is worth isolating individual instances within the ikkyo movement for individual scrutiny. Perhaps the initial entry movement of a certain teacher is isolated. The movement is common to many other techniques and so is a principle. Practising the movement many times by oneself leads one along a voyage of discovery. At first, the movement seems simple, yet, after careful scrutiny, many subtle variations in foot, hip, and hand positions can be discerned that potentially produce slight variations in technique, or henka-waza. A variation ought by definition be a different, yet acceptable approach to any movement. These same variations in movement can then be applied in other techniques. When watching, it is often not easy to see such subtle differences - they need to be felt. Principles can be in terms of footwork, hip movements, body movements, twists, postures, directions, and so on. Another example is time: When performing ikkyo from shomen-uchi; one could cut at the same time; one could cut earlier than uke; one could cut after uke, or, one could start late but overtake uke. As to how early or how late: If uke's up and down striking motion comprises a 360 degree cycle then tori's response can be rationalised as being say, 90 or 180 degrees late, for example. In terms of power: One could cut with the same strength as uke, stronger than uke, or softer than uke. At first, the best practice is to cut at the same time and be of equal power. Harmony comes first but after much practice, one will then be able to change the time, or power. Without harmony there are no options from where to begin, just chaos. In grabbing, uke typically grasps strongly and tori reacts strongly. Both are equal in the beginning, but with practice, tori learns to respond softly, ignoring uke's apparent hardness and not becoming infected by it. These ideas are applicable to all the techniques. Below, are outlines of some of the more broader principles. Other more specific principles are located elsewhere, throughout the text. |

(a) From principle to technique

|

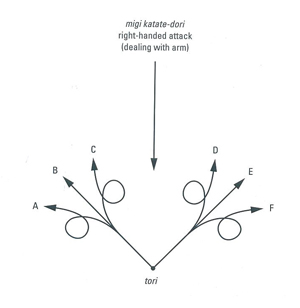

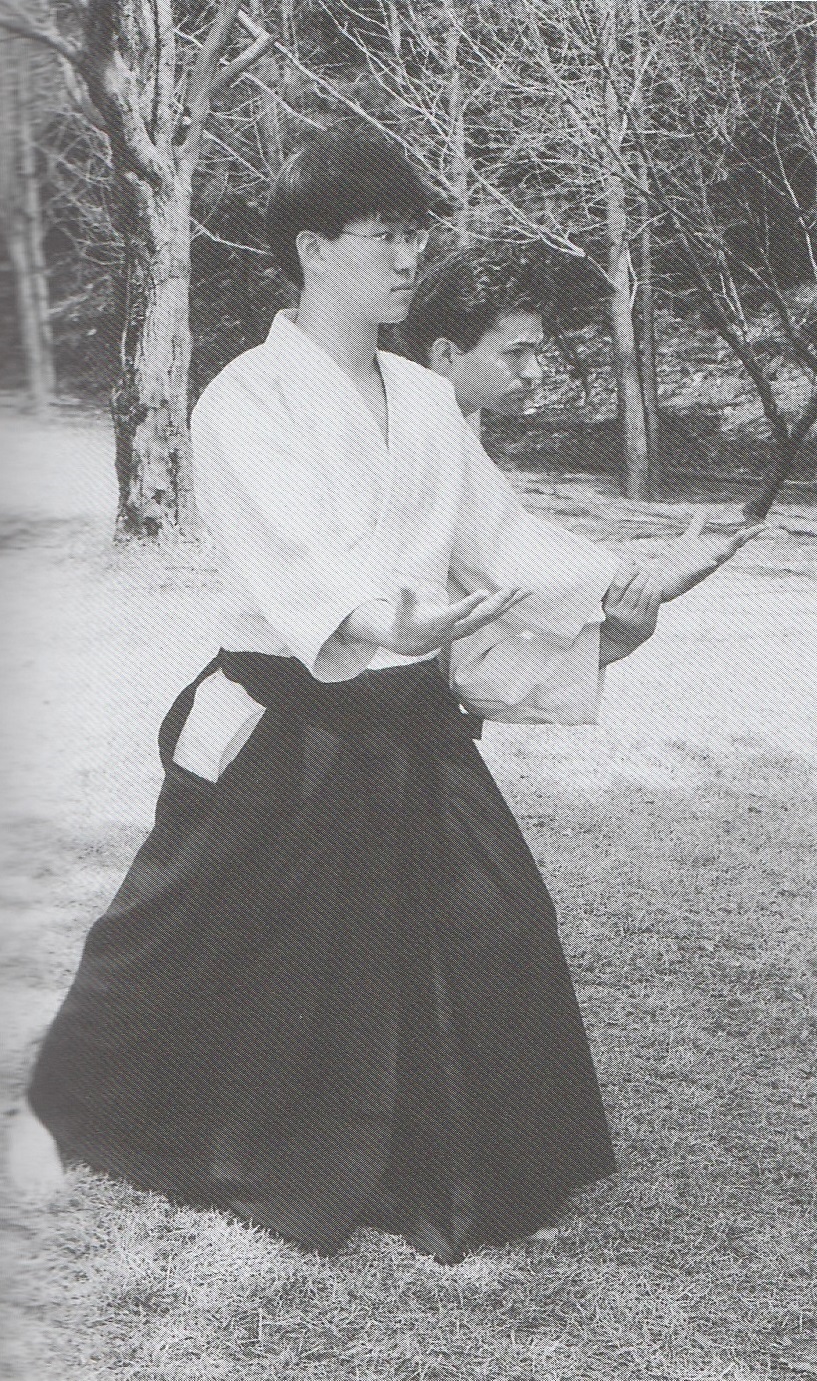

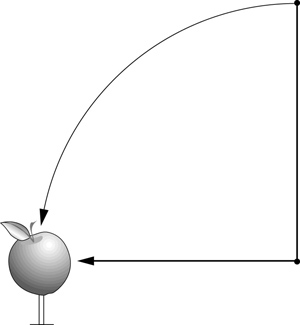

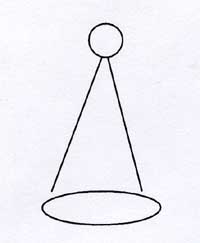

The lines to the left indicate possible directions of movement from a single attack. Starting from say, ai-hanmi katate-dori (or gyaku-hanmi), entering to the front for irimi, tori has the choice of turning clockwise or anti clockwise, resulting in two different techniques. Entering to the rear, tori’s hips can likewise turn either way, resulting in two more different techniques. Such a way of analysing the situation can make otherwise separate looking techniques appear to follow simple easy-to-learn rules of contrasting movement. In this case, we have two movements to the front and two to the rear making a total of four. From these four initial principles begin a great many basic Aikido techniques. Of course, tori might decide to not turn at all while entering, producing yet two more ‘direct’ entry movements.

|

The directions above play out to produce the following techniques:

| A | sankyo | D | kote-gaeshi |

| B | sumi-otoshi | E | udekime-nage |

| C | shiho-nage tenkan | F | shiho-nage |

|

(c) Recognition of shapes Once past the basics, in order to escape the rigidity of the form it is better to refer to the techniques as shapes. Viewing the techniques as shapes allows for more variation in technique but more importantly, this principle aims at recognising a shape in uke that is waiting to be acted upon in the moment. A higher skill is in predicting the shape that uke will present, that is, where uke will be a short moment in the future. Another method is to create the shape that uke presents by either luring uke this way or that, or feigning attack causing uke to respond in predicted manner. To take maximum advantage, the important thing is to be in the right place when uke 'arrives'. Referring to a technique with the more flexible concept of 'shape' will help this become possible since it suggests that variation from the norm, or experimentation, is acceptable.

(d) Kokyu Aiki typically first manifests itself in Kokyu-ho and kokyu-nage practice. Good aiki transcends the technical and is what one feels when the kokyu techniques are performed well. Later, it will transfer over to the techniques and will be felt by a perceptive tori or uke. Kokyu exercises isolate technical detail and focus on simple body movement. When performing these exercises it is especially important to be in good posture and to have fifty percent of your energy in each hand. If that fifty percent can be maintained even though the hand is empty, then it will help with balance, breathing, and co-ordination. The initial contact is the most important be it grab or strike. It is at that moment you should aim to take uke's balance ever so slightly, either mentally, physically, or both. Doing this, always, will give you insight into aiki that cannot be easily explained. But just doing it as robotic waza will lead you nowhere fast. 'Feeling' is everything. Waza is nothing - just technical detail. Three teachers might typically do any kokyu-ho or kokyu-nage in three different ways in terms of footwork and hand / hip positions. If the simplest of movements have variations, then it follows that those same three teachers will do ikkyo or irimi-nage slightly differently, and that these three variations might be explained according to the three different ways they do kokyu-nage. The wise student will isolate parts of the movement and be able to distinguish between, or demonstrate several variations whereas an ordinary student will just have one method and never question it, nor will they notice any differences. And if they do, will likely think it to be wrong. If one is stuck within a particular technique, find a corresponding kokyu-nage and practice it instead; it will probably provide the answer. Kokyu movements are great principles so collect as many as possible, but without committing them to stone. Doing lots of these exercises is the best way to increase your kokyu-ryoku.

|

(e) Tenkan-ho

|

|

| Tenkan-ho from the front. | Tenkan-ho from the side. |

|

This simple turning exercise bores and confuses many, but it holds the key to Aikido. Uke should hold firmly, perhaps imagining pressing a coin against tori's wrist while pressing in slightly towards tori's centre signifying attack. Even when tori moves, the grip must be maintained in such a way that the coin does not fall. By necessity, uke must move their centre forward to maintain the constant ‘contact’ of attack. Tori does not drag uke around - far from it; uke attacks and follows tori as tori evades. Nor is it good practice to swing uke 180 degrees around to the front. Keep uke at the side, blocking their entry with careful body positioning. From here, tori can push or project uke around to the front and start again. Also, tori should make sure that uke is able maintain a comfortable grip – if uke is forced to let go then they will, of necessity, let go and renew the attack. If uke's grip is too strong, one needs to examine the arm positions, being cautious not to struggle directly against uke's yonkyo grip, for example. Offering the hand palm-down is one method that helps tori tremendously. Starting palm-down, move one's body weight forward placing one's own elbow almost over uke's, but ever so slightly to the outside. At the same time, curl the wrist palm-up in the direction of uke's attack towards one's own centre, move slightly to the side and step just behind uke's leading foot and finish by extending both arms equally, as though holding a large ball. Extending unequally will tend to leave tori off-balance - the ball will drop. Another method is when tori offers the hand to uke with the palm sideways, or thumb-up. From this position tori again steps slightly sideways and to uke's rear but this time makes a very small yokomen type movement with the grasped hand. Naturally, it makes sense to practise katate-dori kokyu-ho from various other positions such as from behind, or with the hand thrust upwards in a sankyo-like position etc. Unfortunately, many forget what they have learned in tenkan-ho when practising the techniques. With a good understanding of tenkan-ho one ought to be able to do any katate-dori or ryote-dori technique with ease, no matter what gorilla is hanging on the end of one's arm. If it can not be done, go back to tenkan-ho. A good place to start to apply tenkan-ho in a technique is to investigate and modify the movement of the lower hand of tenchi-nage. Instead of just thrusting straight down to uke’s rear corner, try beginning with a tiny circle as in tenkan-ho before the thrust. After such practice, the straight thrust becomes almost redundant.

|

(f) Suwari-waza kokyu-ho

|

The

principle of tenkan-ho can be used in many situations – note the bottom hand. This exercise proves quite difficult for many. In the same way as the tenkan-ho exercise from standing, what is learned here translates into a broader understanding of how to do Aikido techniques with more finesse. Simple, solid suwari-waza kokyu-ho translates into good Aikido. Standard practice is for tori to work the hands inside of uke’s arms pushing both hands up, or one up and one down. Tori can also work outside uke’s arms, or cross them. Sometimes, tori uses a very strong push to develop strong kokyu-ryoku; this is the less harmonic approach. Here, uke struggles to barely maintain their grip; some criticise this as being non-aiki in approach but such practice is essential as, if done well enough, it teaches one to control the extent of uke’s grip. At the other end of the spectrum the aim is to lead uke in such a way that uke maintains a comfortable grip. Both these extremes form an essential part of the whole and once acquired, naturally transfer over into the standard waza. |

|

Using two hands in suwari-waza kokyu-ho, it is obviously more difficult to synchronise so one necessarily must vary the practice between light and heavy. If 'x' defines tori's ability then uke needs to recognise that and grip just enough to help tori go for 'x+1'. It is a co-operative learning process, not a competition of strength. Viewing suwari-waza kokyu-ho as just another exercise or just another technique will deprive you of perhaps one of the best means of understanding Aikido.

(g) Irimi and Tenkan rationale The ideas of irimi and tenkan (or omote and ura) can be explained in several ways, all of them being legitimate in terms of principles that can be carried over to other techniques. First, irimi is seen as entering uke’s attack and the entrance is made across uke’s front side. Tenkan is made to the rear, across uke’s closed side. Simply, entering to the front or rear gives two different variations of any technique and this is the way most Aikikai schools follow, performing two irimi, and two tenkan variations for each technique. [Aikikai call this irimi and tenkan - Iwama schools call it omote and ura]. Second, is to see an irimi variation as returning uke’s energy back from whence it came – back towards uke; contrasting this, tenkan is the opposite, allowing uke’s energy to continue on along its original line of attack. I personally prefer this idea. [Kyushindo] Third we have them differentiated by uke’s action. If uke grabs and pulls, then tori does an irimi technique; if uke pushes, tori performs tenkan. Contrasting this completely, an advanced Aikidoka can pull when pulled and push when pushed. [Yoshinkan] Fourth, the push / pull idea is limited to attacks made in ai-hanmi and gyakyu-hanmi respectively. In ai-hanmi, uke pulls and tori makes an irimi movement, and conversely, from gyakyu-hanmi uke pushes and tori makes a tenkan technique. [Yoshinkan] Fifth, if tori responds to uke’s attack early then tori rushes in making an irimi technique, if late, a tenkan movement suffices. [Kashima Shin Ryu] Sixth, tori initiates for irimi techniques, and uke initiates for tenkan techniques. Yoshinkan Aikido follows this principle and extends it to the extent that ai-hanmi is the preferred starting point for irimi, and gyakku-hanmi for tenkan techniques. For example, ai-hanmi shomen-uchi ikkyo (ikajo) would see tori (otherwise referred to as shite in Yoshinkan) initiating the attack and performing ikkyo (ikajo). The first three techniques of the Koryu Dai Ichi kata of Shodokan Aikido also show this. In the first technique tori attacks shomen-uchi and makes shomen-uchi ikkyo irimi (oshi-taoshi). In the second technique uke attacks shomen-uchi and tori performs ikkyo tenkan (tentai oshi-taioshi). In the third technique, both tori and uke attack simultaneously, in harmony, and tenkan yonkyo (tekubi-osae) is the result. Seventh, tori always aims to make an irimi technique, tenkan is the result if too much resistance is met. Accordingly, some even insist that there is no such thing as tenkan. I personally like this method. [The progressive school] Eighth, as seen in Kyushido, tori and uke start from shizen-hontai. To take migi ai-hanmi, uke must make a step forwards. However, as uke grabs, tori steps back with the right leg and the result is gyaku-hanmi in terms of the feet. The technique that fits this position is usually a tenkan variation. Also, when uke tries to take gyaku-hanmi, tori steps back and an ai-hanmi foot position is the result. From here, an irimi technique often works best. From this, we can discern the important point that it is the foot rather than the hand positions that give meaning to ai-hanmi or gyakyu-hanmi. Ninth, is the observation that no matter whether one starts in ai-hanmi, gyaku-hanmi, or shizen-hontai, in most schools it is the norm that irimi techniques originate from an ai-hanmi style entrance and tenkan techniques require a gyaku-hanmi entrance, although it is also possible to do exactly the opposite on occasion. [My observation, and it follows Yoshinkan style] Finally, some schools such as Shodokan Aikido and Takeda-ryu Aikido do not really teach in terms of making such strong distinctions between irimi and tenkan. To an observer all these differences might add up to being the same thing, but the way one rationalises it in the mind reflects the kind of Aikido that is produced. Rather than the essence of aiki being different, the above are differences in style, or learning method. Each of the above is a legitimate principle that I have experienced in the various schools I have visited, and all, from principle to no-principle, can be used as independent principles in one’s training. The curious ought to experiment with variations not found in their own art.

|

|

(h) Sokumen

| Sokumen means side-entry and appears to fit mid-way between irimi and tenkan movements. In basic sokumen, one typically ends up in a position ninety degrees with respect to uke’s line of attack, but in practice it can vary considerably. Few schools use it, less adopt it as a principle that can be used in other common techniques from ikkyo to kote gaeshi etc. An important distinction is that from a sokumen entry, tori often has the option of going for either an irimi or tenkan movement – it is a central position, a junction. For example, when doing sokumen irimi-nage, at the central point of balance taking, take a pause, and examine how one could throw either forwards or backwards, or change to different waza such as ikkyo or shiho-nage. Sokumen is subtle, quick, and safe. Tori evades and is in a position to respond immediately. It is an excellent position that is extremely useful in more practical applications, especially against punches and kicks and for general self-defence. Frankly, I am surprised it is not used more. It is a great principle. |

|

|

|

|

Sokumen entrance is from the side. |

|

(i) Junctions Mid-way through many movements one can find common junctions that link techniques. Rather than just sailing through a particular technique, it is important to pause and ponder at these junctions. If one just does shomen-uchi ikkyo from beginning to end with no other thought, the point here will be completely missed. The initial avoidance creates a junction; the initial meeting creates a junction; the cut down creates a junction. Learn to recognise and create junctions; from here one could do the required technique as being taught by the teacher or switch to another.

(j) Symmetry of techniques The techniques correspond to each other in terms of symmetry and this principle is very useful in developing combinations. For example, if uke's right arm rushes forwards and one receives it in right posture and rotates it clockwise, then one may end up with ikkyo, and if it were a left, then one might end up with kote-gaeshi, or shiho-nage. If there were no resistance to these initial moves, then the technique would be carried through to completion. If uke suddenly began to resist and get up the ikkyo might be switched to irimi-nage, etc. There are many possibilities and it depends upon where one is in relation to uke and what 'shape' one recognises in the moment. Here, the principle is to rotate to the right, the technique being determined by what uke does next. This is possible due to the inherent symmetry between techniques. Also, in terms of counters one need look no further than one's own hands. We often twist our own hands or arms to their extreme in the process of making technique and accordingly, there are many opportunities waiting to be taken by a smart uke. Think about this: If someone is doing nikkyo on you, you are in fact, only a few millimetres away from doing nikkyo on him. Likewise, if someone has sankyo on you, you are only a few millimetres away from getting kote-gaeshi on his hand. Of course, the one who has it 'on' has the advantage, but if he makes a mistake the opportunity is only there if you know it is there.

(k) Arm shapes Uke’s arm typically presents itself in four positions. Palm-up, thumb-up, palm-down, and thumb-down. One more position is palm-up at the opposite extreme, forming an ude-gatame shape. It is unlikely that uke would present tori with such a shape as it would be too obvious an opportunity, but the shape does exist, waiting to be created. If tori can distinguish between the shapes as presented by uke as they approach, a suitable technique can be applied accordingly.

(l) Equal hands By this is meant having equal energy in each hand. When doing techniques, if tori has more energy in one hand than the other when pushing, they may twist too far and/or become off-balanced slightly. Accordingly, though one hand is empty, both should still be extended equally. This principle should be applied to all techniques. In Judo, one principle is to attack the weak side of the body. If one feels that the opponent has too much energy extending from their right side, immediately attack their left as it is vulnerable.

(m) The magic of three Many movements can be rationalised in terms of three. Arms, legs, hips, and head rotate either to the left or right or remain at a neutral point in the middle. When thrusting with the sword the blade can be straight, twisted to the left, or twisted to the right. Timing can be early, in harmony, or late. Techniques can be done in terms of jodan, chudan, and gedan. Breathing can be relaxed, focused, or in the form of kiai. Striking can be hit and retreat, hit and transfer momentum, hit and follow through. Tori can immobilise uke, tori can project uke, or tori can let uke escape. Tori can push, draw, or deal with uke on the spot. Tori can perform most of the movement, tori can stand somewhat still and make uke do most of the moving, or both tori and uke can move somewhat equally. In space, uke can be in front, to the side, or to the rear. When tori moves with respect to uke the movement can be analysed as turning like two meshing cogs or gears, or turning like a chain on two sprockets, or linearly. It is possible to dissect movement in this way and it helps in analysing technique in the midst of movement. In rationalising movements like this it becomes clear that when performing say, a right handed ikkyo or irimi-nage, one's hips, arms and legs are all generally moving clockwise at the moment of contact. Being aware of how one moves makes it easier to see what the teacher is doing. It also becomes easier to discover variations that follow Aikido principles.

(n) Immobilisations All five basic immobilisations follow the path of ikkyo and controlling the elbow is a key element in each. For example, when taking nikyo, try to guide uke's elbow through a similar trajectory to ikkyo. The same can be said of sankyo, yonkyo, and gokyo. In irimi techniques, one must be careful not to give uke's energy directly back to them, otherwise it may result in a clash and/or uke will regain composure. Some schools have a sixth immobilisation, rokkyo, otherwise known as waki-gatame (an armlock more common in Judo), a devastatingly useful technique that can be done almost instantaneously when any of the basic five fail to work. Arm-locks are often frowned upon in Aikido but they can be done by extending rather than locking thereby making them more acceptable to the doubters. In fact, done in this way one can add far more power safely – always good practice for self-defence. A simpler arm-lock is ude-gatame, sometimes known as ude-hishigi. Interestingly, for effective arm-locks, one has to find the path of most resistance to apply pain.

(o) Projections In projecting, uke flies off at a tangent centrifugally. Getting rid of ukes in this way allows faster practice, such as in ninin-dori. Of course, it is possible to throw down centripetally as in Judo, but then it is necessary to keep one's attention right there and immobilise since uke would be dangerously close. When projecting with the jo, push along its length; bend the jo too much and it will break. When projecting with kokyu-nage one’s arm works in just the same way. After throwing, one’s posture can be either forward or central. Don’t just let it happen; make a rational choice and practice both. Your posture ended up forwards or central because you wanted it to.

(p) Still techniques Most people have a mental picture of which direction they should move in relation to uke. In basic technique, it is tori that does most of the moving. Practising without moving the body adds another dimension. Try sitting in seiza or standing in shizen-hontai and let uke take one's wrist from the side as in gyaku-hanmi. Rock towards uke slightly making contact, and then drop back, drawing uke's hand in front while sending them behind as in shiho-nage, then bring them all the way around to one's front and throw. Here we have shiho-nage, yet tori hardly moved. Trying it again from ai-hanmi produces ikkyo. Not really practical as techniques, this kind of practice helps develop aiki. It is also good preparation for understanding the more realistic situation where both tori and uke move around in unison as the technique unfolds - mid-way along the continuum.

(q) One technique The concept of ‘one technique’ being used to incapacitate uke is prevalent in Aikido, even if it is not clearly stated. Here, uke’s attack is so determined that tori can easily produce a single technique to deal with it. Accordingly, many schools, if not most, train to deal with a single clearly defined attack with the idea that one technique controls it. And most time, sometimes years, is spent trying to figure out how to refine such perfect technique until it works. In concept, it is quite a realistic and necessary principle to aim for, but in practice, it fails to prepare for a more cautious uke that does not over commit. The overbearing idea of ‘one technique’ explains why, in Aikido, few combinations are taught in any structured fashion. It makes sense to be aware of such limitation.

(r) Displacing uke When performing kokyu-nage it is useful to take uke's place. For example, when projecting as in morote-dori kokyu-nage, as one steps forward to throw, move the hips slightly into uke's space, and the feet follow. As uke disappears, one assumes uke's previous space - one has displaced uke from their spot. This also has the effect of making the projection slightly spiral in nature and is also excellent entering practice for koshi-nage. Having displaced uke many times in kokyu-nage, one will soon realise that it is possible to perform a similar movement in say irimi-nage, or tenchi-nage. With a little imagination, this principle, the feeling of displacement, can be applied in most other techniques, even ikkyo. On acquiring this principle, entering further still a whole new range of koshi-nage type techniques will emerge, such as say, ikkyo koshi-nage.

(s) Kuzushi & tsukuri Common in Judo or Shodokan Aikido, these 'terms' of breaking balance before making technique are seldom heard in the more 'traditional' forms of Aikido. Of course, the balance must always be broken but in sport styles it is more imperative, otherwise one will never be able to throw a resisting opponent. In the traditional styles it is uke's zealous singular committed attack that is used. Here, uke may even over extend, off-balancing themselves. This is intended to match the kind of outright committed attack one would receive on the battlefield.

(t) Hard or soft A common analogy of ki is water coming from a hose. Whether it comes out under high or low pressure its essence remains unchanged - it is still water. The skill then is to be able to increase or decrease one's pressure, or energy, while maintaining essence, or flexibility. Some people insist on always working only at low pressure, others only at high pressure, but such thought restricts development. A runner sometimes runs slow and sometimes fast. His aim may be to increase his speed, but running slower will still be an important part of his training - he can not run fast all the time. In reality, one's techniques will be a never-ending change from hardness to softness and back again while moving through the various stages of a technique. To the self one's aiki should feel soft, to one's partner it should feel as hard as nails, but in a polite kind of way. To an onlooker, it may look as though uke took a dive. Just as there is no hard or soft water, there are no hard or soft styles or techniques, the two are inseparable; heavy and light waves flow into each other. People often talk of hard or soft styles or hard or soft training. The usual context for such discussion is that some schools train harder than others, insisting that their method is the better. The hard think the soft are fairies; the soft think the hard are stiff gorillas. If all one does is soft Aikido then one will likely be an aiki fairy, and if all one does is brutish Aikido then one will indeed be a gorilla. It is as simple as that. As is usual, common sense lies in compromise. Practice both extremes and exist somewhere in the middle. If one must only have one aim, be neither hard nor soft, just be vigorous. Quite often, both the so called hard or soft schools can be just too slow. One should also be flexible in approach: Train hard with the strong, vigorously with the fit, and gently with the frail.

(u) Large or small circles Aikido consists of many movements that can be branded as being either large or small circles. Large circles involve large rotations or sweeping movements of the body, arms, and legs; small circles are described by smaller, tighter movements. Many equate the smaller movements as focusing only on the wrist but this is a mistake; the smaller movements are inclusive of body, arm, as well as the wrist. Both offer insight and it is a great disadvantage to overly practice one in preference to the other. Indeed, it is possible to put small circles into large movements mixing large and small together. Further, combining arm and body movements creates spirals (see Generating Power).

(v) Distance Where one is in the moment goes some way in deciphering the available shape one recognises in uke. For example, kote-gaehi is done from an arm's length or so from uke, for shiho-nage one moves closer, for irimi-nage one traverses behind. |

(w) Straight line or a circle

|

As to which is faster, an attack in a straight line or a circle, think of this. First, isolate the feet from the equation – do not move. Now, if one thrusts with a sword at a target the hands must cover a distance of say, one foot in a straight line to strike. Next, if one delivers a downblow to that same target from above the weapon may move through a distance of three feet or more while the hands move through about say, a similar one foot of distance. The point here is that the blow, travelling through a longer distance, has gained a lot more momentum for a similar amount of hand movement. No doubt the thrust is faster and the downblow more powerful, but with hard training the speed of a downblow improves considerably.

|

|

|

A direct thrust is quicker, but not as powerful as a downblow. |

|

As is usual, the faster is likely to be the one who has trained harder. Even if we determine the thrust to be better, it must be remembered that in European duels of olde, rapier duellists, while boasting of their speed, typically suffered several thrusting 'hits' before being incapacitated whereas the result of just a single heavy sabre blow was far more debilitating.

(x) Pain Pain is a great principle. Once the technique is on, it should stay on for the whole technique. If the technique is not on, uke should stand up. Nikyo is one of the most painful Aikido techniques and should be performed quite differently to ikkyo. With ikkyo, one leads uke's attack down to the floor along their arm. Nikyo is similar but a pain factor is added. This time, in addition to what one has learned in ikkyo, uke is led by pain, all the way down. It need not be excruciating, but it has to be 'on,' otherwise it is false. And when applying the pain, for irimi one applies it in such a way that uke opens up for an irimi entry. Conversely, for tenkan, one applies the pain drawing uke forward towards one's own centre, then moving to the side enabling a tenkan movement. One should not push the pain towards uke for tenkan because that would necessitate an irimi technique. |

(y) Weapons

Weapons teach imperative avoidance. Teachers can tell students to 'avoid' a thousand times but they never do it, yet after only a few lessons training with weapons any student will soon begin to understand. One need not be a master swordsman to be able steal the principles from weapons movement and apply them to Aikido. No one will escape a few raps across the knuckles, and all will have a wary sense of the point. The result is a natural avoiding movement that can easily be adapted to Aikido as uke strikes, takes hold, or both. Another interesting way to practice is for tori to take a bokken when doing ninin-dori. All tori has to do is avoid slightly and cautiously chop the ukes who just walk in. Doing this is great practice for avoidance, for developing irimi and taisabaki movements, and it also teaches important lessons in distance - even with a bokken one has to be surprisingly close to uke to strike. Practising with a jo allows both tori and uke to make or receive powerful hits fairly safely. One learns not to block, but to deflect or parry. And one need not parry if one has confidence in avoidance. Indeed, one need not even avoid if the combined parry-strike is strong. Also, when thrusting one does not strike randomly, one must have a defined target. Another way to practice is where uke grabs tori's jo. Tori projects uke according to the movements in Aikido, in the spirit of kokyu-nage. The simpler the technique the more one will learn; complicated techniques are too contrived and not useful. Here, both hands must contain equal energy and must push along the jo - the direction of the jo's strength. If the jo bends or breaks, consider it bad technique. It may bend slightly, but less or none is better. Why? Consider pushing along the jo as being equivalent to projecting with kokyu-nage using one's unbendable arm. Consider bending the jo as using one's strength. Practice combined with careful thinking will make it clear. Keep form simple - learning complicated weapon forms with or without a partner before getting the hang of the basics is the sure road to ruin. What is learned in the beginning sticks like glue, and if learned wrong, then it will stay wrong for a long time. It is very hard to recognise, let alone undo, a bad habit. If one must perform a long weapon form, think of it as a library of separate techniques, break it down and practice its shorter constituent parts. With short weapon forms it is far easier to get a feel of the movement. Two or three movements concentrating on one detail should suffice. One major problem is that many people carry themselves differently when using weapons. In Aikido, what one does with the bokken and jo should correspond exactly to what happens in ordinary Aikido practice. If it does not match, then something is wrong, and one will develop contrary bodily movement habits that will serve only towards confusion and even if one trains for fifty years one will never know what one is doing. |

|

The fact that people of other arts sometimes have aiki yet do not know they have it is quite interesting. In reverse, some Aikidoka have attributes that are found in other arts like Taichichuan, Pakua, Wing Chun, or Jujutsu. While the external forms obviously differ, these arts do share some similar internalised principles. Therefore, training in another art can enable the discerning Aikidoka to be more aware of what they might already know without knowing. Of course, in the beginning the arts will seem quite separate, and many may like to keep it that way. After time, forced separateness may deem them incompatible, but reasoned thinking will allow an exchange of similarities, or principles, to take place in the direction of the favoured art. Accordingly, practitioners will then have an idea of how to recognise, describe, and pass on such principles that were hitherto apparent, yet unrealised. The most important thing to remember is that in borrowing, one takes the principle but not necessarily the form. |

(z1) Circular Vs Linear Power

|

A:

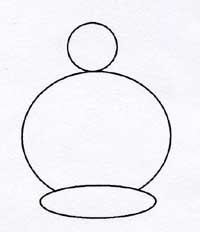

The oval represents tori's shoulders. The large circle represents

tori's outstretched arms, meeting at some comfortable point in

front at shoulder height. The small circle represents the point of

contact on uke; it could be a wrist, an elbow, a shoulder, the

jacket, the body, or the head. The important thing to note here is that

uke, or the targeted part, typically body or head, is outside

tori's circular zone of power. If uke does not allow himself

to be drawn into tori's circle, for best technique tori has no

choice but to extend his arms to develop power (see C below) for a more

linear technique. One other alternative is D (see below).

|

|

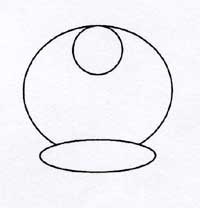

B: In

the next diagram, tori contacts uke's wrist, elbow,

shoulder, body, or head inside the circular zone. Here, uke is

more easily brought under control as tori can utilise his

circular power more efficiently. For efficient technique, tori

maintains circularity in his arms and performs a circular technique. In

Judo, think O-goshi with one hand curved behind uke's

neck. In Aikido, think kote-gaeshi with uke's wrist in the

circle, shiho-nage with uke's elbow in the circle, or

irimi-nage with uke's head in the circle.

|

|

C:

Here, tori's arms are extended forward. In this position, tori needs to

make technique with linear movement, not circular. In Aikido, think

sumi-otoshi or shomen-ate. In Judo, think ippon seoi-nage

or kata seoi-nage. Or, as in B above, think kote-gaeshi,

shiho-nage, and irimi-nage etc, but linearly. This

position demands that tori adopt a linear technique, which may or

may not, at some point, bring uke into tori's circle thus

necessitating change.

|

| In Judo,

contestants usually meet as in diagram A or C. Many struggle to make

their circular techniques work for years and never realise the futility

of these positions for circular techniques. What they need to do is to

move uke in a linear way to throw, or, to move uke

linearly and manipulate the distance such that uke enters the

circular zone, as in B, to become the 'victim' of a circular throw.

After years of training, a Judoka's body will come to distinguish these

differences even if his mind does not -- he will throw well, but may not

know why, and will not be able to teach it efficiently. In Aikido,

however, 'friendly resistance' makes it even more difficult for the

body, let alone the mind, to determine the true and the false in terms

of distinguishing between the circular and the linear, with the result

that people wander around in darkness, not knowing why something works

or not, or worse, not even having their attention drawn to such a

question. Thus, beyond beginner, a compliant uke is your enemy.

|

|

| D:

Typically starting from A above, tori pulls uke towards

himself and wraps uke around himself, much like how the drum of a

crane wraps the cable around itself, or, like how a fishing reel winds

in the line. Here, tori becomes the drum or reel, and uke

is drawn in and thrown off centripetally. Uke is still outside

tori's circle of power. However, tori could also quickly

change his arm position to bring uke within his circle of power

and still use this same reeling in idea.

It is also important to note that when uke is within tori's circular zone, so tori may fall within uke's. Thus, better is he who knows his situation, better is he who has developed the knack to work in this situation, and better is he who has an appropriate technique. Also to note is that when training the sword, you can hold it with arms extended linearly, as in C, or you can hold it with arms curved, as in B (feeling the sword to be inside your circle). D would be close to a hasso position. None is more correct than the other, each has its place in training logic. To say one is wrong and the other right is to say you do not understand. (z2) Remove power from your turning (also mentioned in the Power chapter). Remove it completely. No power, just coordination. A coordinated set-up. While there are various ways tori can apply power in a turn, especially in say Judo, just stop for a moment and try this way of redefining your application of power completely. Basically, when you meet uke's incoming line of force, just meet it and allow it to turn you lightly. Remove any thought of applying circular power. Rather, use uke's 'push' or 'intent' to align your centre with theirs. Then, once aligned, you are instantly set up to apply a more linear power, applied in the direction set between you feet. Of course, circles are everywhere, so, limit this idea to your spinal rotation. Set your spine free - let it rotate left or right freely, but once lined up with uke, you can apply your linear power efficiently - and it should be almost instantaneous. To be more effective, you could neutralise uke's power by adding a subtle minimum to uke's incoming energy, redirecting it slightly, but not with the spinal rotation - more of a linear hand movement from your centre. After a little practice, if you turn freely according to uke's attack (not avoidance - you need their pressure to push you), uke will line your body up for you to counter their attack. This method could easily be in the aiki section. |

|

|

(z3) Going too far Bruce Lee claimed to teach only the essence of Wing Chun, disregarding less essential elements that he deemed were unimportant - but would his students not be rather curious as to what he had discarded? After all, it was his skill in Wing Chun that made him famous. It is up to the teacher to teach the totality of the art. It is up to the student to decide whether they like it or not - which more often than not is based on what they can physically do. But that same student, on becoming a teacher, has the same responsibility to teach the totality. What that means is, if one does Karate and cannot do high kicks, then one should not become a teacher. A student can abandon a principle if they cannot physically do it, but a teacher must beware since a teacher has to teach the principles. Therefore, as a student one can get away with saying, "I do not believe in high kicks," but a teacher of that art has to be able to do them, and do them well. In fact, a teacher has to be able to disprove the "I do not believe in high kicks" argument and show that they can be done, that the said principle can be shown, and with power and grace. There are many people out there who can do excellent high kicks. Do not blame the technique; the answer is closer to home - just admit that you cannot do it. |

|

(z3) Aiki Re-read the aiki section. I define aiki as the ability to recognise, manipulate, and control uke's energy to their demise. If you can also find away to 'stimulate' uke's energy you will find it much easier to control them.

|